There is power in “bottom-up” employee improvement, but it doesn’t get widely or easily embraced by organizations, meaning missed opportunities for improvement.

That was the topic Mark Graban, our vice president of Improvement & Innovation Services and founder of LeanBlog.org, discussed during a recent KaiNexus webinar, Strength in Numbers: Improving from the Bottom-up, hosted by KaiNexus CEO and co-founder Dr. Greg Jacobson.

In today's post, we'll take a look at the high points of that webinar.

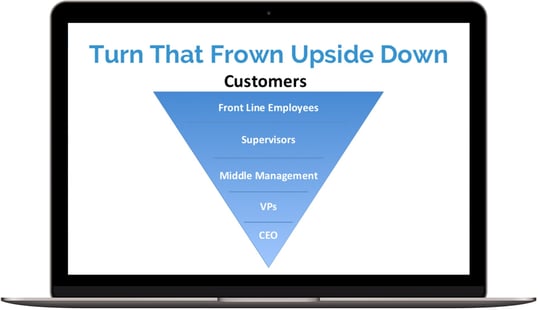

The “Top” to “Bottom” Pyramid

The “bottom” of bottom-up references the typical pyramid illustration used to visualize the management structure of an organization. That pyramid usually places the CEOs and executives at the top point of the pyramid, which then gets wider through the many management levels before the base layer of frontline staff at the bottom. Mark explained that to combat the hierarchical, and potentially insulting, placement of staff at the bottom of the pyramid, some organizations try to invert the diagram so that frontline staff, and sometimes even customers, are labeled at the top.

The “bottom” of bottom-up references the typical pyramid illustration used to visualize the management structure of an organization. That pyramid usually places the CEOs and executives at the top point of the pyramid, which then gets wider through the many management levels before the base layer of frontline staff at the bottom. Mark explained that to combat the hierarchical, and potentially insulting, placement of staff at the bottom of the pyramid, some organizations try to invert the diagram so that frontline staff, and sometimes even customers, are labeled at the top.

“We can draw whatever number of shapes we like,” Graban said. “If the organization just changes the drawing but doesn’t change the mindset, then that’s going to get people discouraged, that’s not going to lead to a culture of continuous improvement.”

Top-down improvement falls in line with command and control leadership, Graban explained. Command and control leadership holds the notion that executives are the smartest employees in the organization and therefore they make the decisions, and if employees would just do what they were told to do, then the organization would have superior results.

Listen to this Post and Subscribe to the Podcast:

A Problem Solving Problem

“Executives need to help frame strategy and direction for the organization,” Graban said. “That’s important, but when the 'how' gets communicated or pushed in a top-down way - of how do we solve problems, how do we improve performance - we can often get into a lot of trouble.”

Graban gave the example of a piece of carpet that was installed in a hospital embarking on their Lean journey about 10 years ago. To solve the problem of noise in the hallway disrupting patient satisfaction at night, executives had a piece of carpeting installed without even telling the manager on the floor.

“It wasn’t about looks, it was about reducing noise, it was about improving patient satisfaction, those are important goals that can and should be defined in a top-down way, and cascaded through the organization. But what makes a culture of continuous improvement happen is when we challenge a team or employees to solve a problem and to figure out something on their own.”

What’s worse, there was another top-down mandate that said the employees had to roll portable computers around the area, which was made more difficult by the new carpet. This meant one top-down mandate conflicted with a different top-down mandate.

When the hospital looked at the patient satisfaction data for the hallway, satisfaction did improve, but it did so a month before the carpet was installed thanks to several other smaller improvements already implemented by frontline staff. In the end, the carpet had no visible effect on patient satisfaction in the data.

The 80/20 Principle

Data proving that bottom-up improvement has more of an impact on success is available. For those in organizations that would need to be shown research that proves bottom-up improvement works, Graban recommended the book The Idea-Driven Organization: Unlocking the Power in Bottom-up Ideas by Alan G. Robinson and Dean M. Schroeder.

“Robinson and Schroeder call that the 80/20 Principle, but they’ve found it in a lot of different types of organizations. They started collecting data whenever they came across it, and found it to be consistent in services, manufacturing, health care, and government, lots of different settings,” Graban said. “So they have consistent findings that bottom-up improvement is powerful. This doesn’t mean it’s easy; when we talk about change in the organization, change of any type, even personal change, something being factually correct doesn’t lead to easy acceptance. What’s rational, what’s logical, what’s factually true, doesn’t necessarily automatically easily happen in an organization. That’s why organizational change is so difficult.”

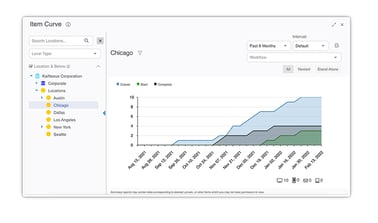

Looking at KaiNexus statistics, Graban explained that one in three improvements made by KaiNexus customers has a financial impact. In addition, 54% of all improvements impact quality, 13% of all improvements increase the safety of staff and customers, and 54% of all improvements increase staff and customer satisfaction.

“So if people think bottom-up ideas are nice to have, we might try to show them data that shows small ideas can actually have a big impact. But again, that being factually true doesn’t lead to easy acceptance,” Graban said.

Why Don’t We Have More Bottom-up Improvement?

The reason for not having more bottom-up improvement is not with employees, but with the system, or even with the leadership mindset, Graban explained.

“They might think that improvement is a job of the leaders. So, we might present data that shows bottom-up improvement is powerful,” Graban said. “Then the leaders might say, ‘ok, I’m going to tell them to participate in improvement. And I think alright, let’s look up dictionary definitions of irony.”

Why Are Leaders Pushing Improvement From the Top-Down?

The reason leaders may be pushing improvement from the top-down is because of a natural reflex called the "Righting Reflex," Graban explained. This reflex is the desire to fix what seems wrong with people, or an organization, and set them on a better course by directing or telling them what to do. Unfortunately, while natural, this approach leads to defensiveness, which is also natural.

The core textbook that discusses the Righting Reflex is Motivational Interviewing by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick. Motivational Interviewing is an approach that comes from counseling, specifically addiction counseling, that aims to work with people and help them decide to move from ambivalence to action

People tend to feel bad when approached with the Righting Reflex, and causing them to feel bad doesn’t make them want to change. We think we’re doing the right thing, and it turns out to be counterproductive, Graban explained.

“Telling people what to do often leads them to think about why they can’t do it, which again is counterproductive. So, we need to shift from wanting to be right,” Graban said. “Feeling right about something doesn’t really feel good compared to helping people change.”

Another resource on Motivational Interviewing that Graban referenced was MI Lead: Motivational Interviewing for Leadership. For those interested in learning more about Motivational Interviewing for their Lean efforts Graban recommended reading it first. In that book the authors J. Wilcox, B.C. Kersh, and E.A. Jenkins reference a 2014 research study that proved human beings are hard wired to prefer their own ideas over those produced by others.

How Do We Evoke Change without Telling?

Quoting MI Lead, Graban explained that an “evoking style” elicits information about the what, why, how, and when from people instead of imparting that information onto that person, or telling them what to do.

Some examples Graban gave of evoking questions included:

- What do you think we could implement?

- What possible improvements are important to you?

- Why is it important to you to improve?

“Questions like this end up being more effective, and they fall into what’s described as the 'Spirit of MI' (the spirit of Motivational Interviewing). This reminds me of what I’ve heard described as the spirit of Kaizen or the spirit of Lean,” Graban said.

The spirit of MI includes:

- Collaboration between the practitioner and the client

- Evoking or drawing out the client’s ideas about change

- Emphasising the autonomy of the client

- Practicing compassion in the process

“We might have something that’s correct, and awesome, and helpful, but if we push those helpful, good ideas on others we shouldn’t be surprised when they’re resistant. We can try to figure out what to do to create an environment where people choose to change,” Graban said.

This article is just a summary of the many ideas around Motivational Interviewing, for more information we recommend you watch the webinar in full. Watch the full webinar here!

Add a Comment