With a title like How to Leverage Lean for Long-term Success (Under Short-term Pressures), it’s no surprise that our recent webinar was packed with some useful information and actionable advice for viewers. Hosted by our VP of Improvement & Innovation, Mark Graban, the webinar was presented by Warren Stokes, Director of Process Improvement at HonorHealth, a health system in Arizona and KaiNexus customer.

Watch Now (you can watch the recorded webinar immediately after registering):

How to Leverage Lean for Long-Term Success (Under Short-Term Pressures)

In this webinar, you'll learn:

In this webinar, you'll learn:

- How to leverage the intellectual capital and experience of your frontline employees first

- To not over-complicate your Lean improvement with too much of the scientific and not enough of the practical

- Why it’s important to build trust and support for continuous improvement

- How Lean best fits into a larger, long-term continuous improvement strategy in a way that avoids succumbing to short-term pressures

- How leadership and a Lean team can create and empower laser-focused energy

The Plot, the Approach, and the Opportunity

Stokes began by outlining the plot that shapes the story of many organizations today across various industries. As he explained, outside pressures - policy, technology, legal considerations, market changes, budget gaps, decreased demand, decreased volume, increased supply costs, etc. - can create a situation where leaders are under pressure internally to respond to the short-term outside pressures rather than focusing on their long-term goals.

“There should be no difference in the short-term versus the long-term in our commitment to Lean; we should be adding to our longer-term strategy,” Stokes said. “There’s a couple of rules, or principles, that we would want to follow in order to be as successful as we can, or as effective as we can in the short-term.”

The first principle is not to focus on a one-fell swoop idea, Stokes explained. Usually, if there was one viable big idea it’s likely that the organization already would have implemented it in the first place anyway - and if they haven't, it's because it's is usually too big of a risk for the organization.

The second principle is to be mindful of organizational disruption when considering improvements and cost reductions. While everything an organization does has some sort of impact, the degree of disruption and how healthy that disruption is for the organization should be considered.

Defining the Problem: Identify Critical Information & Prioritize Simply

The first step, before we even get into planning, is to align - and to align quickly - Stokes said. This begins with getting a true understanding of the current state of the organization by focusing on the key business drivers that are driving the business or reflecting the business, and by validating the definitions and calculations.

Once an understanding of the true current state of the organization is reached, the organization needs to take the data it is receiving and add context to turn it into useful information. As Stokes explained, data itself is fine, but it’s like a bunch of pieces of a puzzle; if we don’t know what picture the puzzle will reveal, it’s harder to make those decisions.

“One other piece of this would be prioritization. Once we understand what those key business drivers are, once we understand the picture and the context of what this data is showing us, we want to prioritize because we can’t focus on everything, especially in the short-term” Stokes said, offering a variation of a simple failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) chart to illustrate how to quantify the impact of actions on each key business driver.

Effective Use of Lean Language: Simple and Practical

“Part of leadership’s role is to create the right energy. We want everyone focused, and we want to get everyone in the mindset. There’s already anxiety and it’s already a stress-filled environment [due to the] short-term pressures,” Stokes explained. “A very critical part of what [leaders] do is provide clarity around the situation… using effective language and bringing visibility, or light, to the challenges ahead of us... not just focusing on one level of the organization, but rather, engaging at all levels.”

When an organization focuses on just one area that’s struggling, there is a risk of stakeholders feeling targeted, Stokes said. If they are viewing it that way and feeling anxiety, they will disengage further and won’t be as motivated, meaning the organization won’t be able to capitalize on all their experience and knowledge. Stokes said that to combat this, leaders should be specific about the challenges the organization faces, and avoid generic phrases like, “Work smarter, not harder.”

Speaking about the effective use of the language of Lean, Stokes cautioned it can be a barrier when the jargon heavy language of Lean experts is used to explain things to those new to Lean.

“If we’re trying to be as effective as possible within our own organization, the language of Lean is the language of the organization - and it’s up to us to bridge that divide. What we don’t want to do is create a new barrier while we’re under these short-term pressures, where now we’re actually trying to teach people a whole other language while trying to also get them to problem solve,” Stokes said.

Executing with Rapid Cycles of Improvement

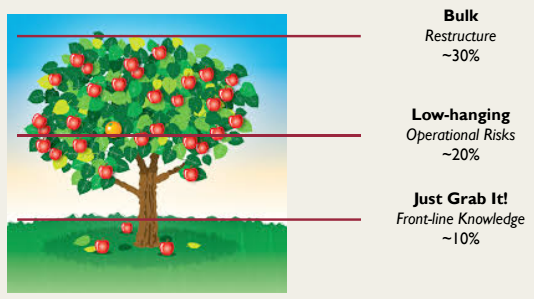

After the problem is understood, the energy is there and a simple, unified improvement language is being spoken, it is time to seize the opportunities for improvement. Stokes described the typical opportunities for being able to respond to short-term pressures by using the analogy of a fruit tree, which can be divided into three levels:

After the problem is understood, the energy is there and a simple, unified improvement language is being spoken, it is time to seize the opportunities for improvement. Stokes described the typical opportunities for being able to respond to short-term pressures by using the analogy of a fruit tree, which can be divided into three levels:

- Fruit lying on the ground: Representing about 10 per cent of cost reduction opportunity, utilizing the knowledge of front-line employees who know their work and can make easy improvements based on intuition, knowledge, and experience, represents a type of improvement that is just lying on the metaphorical grass waiting to be grabbed.

“The key is removing that barrier for them, opening up the gates, allowing the flood of the ideas that they’ve probably had for many years or for quite some time to flow,” Stokes said. “These will surely be very incremental ideas, but as they all add up we can see the cumulative impact of roughly 10%, which is quite large in sum. And by the way, this also builds the moral, it builds trust, it builds empowerment among the team.” - Low-hanging fruit: Representing about 20% of cost reduction opportunity, operational risks represent the low-hanging fruit on the metaphorical tree.

“This is where we really focus on the waste itself,” Stokes said. “Another piece of this would be meetings. How much are we tying up our current talent? How much are we over-processing with all of these meetings? We’re expecting our leadership, especially on the front-line, to go out and problem solve and to get results during this time, and yet we’re pulling them away from there and putting them in meetings. And then aligning your daily management to ensure that we’re optimizing this, and leveraging this as much as possible."

Stokes suggests narrowing and focusing attention on a few key indicators and using visual indicators like a dashboard or another visual system to monitor progress. - The harder to reach fruit: About 30% or so of the cost reduction opportunity in the system lies in process restructure across multiple departments and across functions. This fruit sits at the top of Stokes’s metaphorical tree.

“We’ll begin with first understanding what your requirements are,” Stokes said. “Often it’s the communication that I see in a process, that is the number one driver of rework or longer turnaround times or longer processing times. That communication often comes from the supplier and the customer not fully understanding what is expected from each.”

Stokes took viewers through an example SIPOC (Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs, and Customer) template, which is a tool that can be used to align customers to suppliers and also make rework visible.

Stokes also recommends short cycles of improvement that are about two-weeks, which is visualized through story boarding or creating an A3 for each chunk, making it visible and then running a Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle for each cycle of improvement.

Stokes illustrated this small, rapid improvement cycle adding up by recalling the story of the Crow and the Pitcher. The crow, wanting to drink the water he couldn’t reach at the bottom of a pitcher dropped pebble after pebble into the pitcher until the water rose to the top, showing how small improvements add up.

“The fact is that we can’t afford not to be Lean, especially in the short term,” Stokes said - which is a great point to end this summary on, in my opinion. For more information, be sure to watch the webinar in its entirety!

Add a Comment