Wow! The daily lessons served up by the current political climate in the United States just keep coming. I’m quite certain nobody intended to help us gain these insights, but why bypass the opportunity! So here we go.

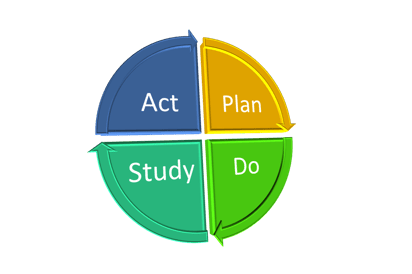

Some people call their improvement cycle PDCA, as outlined by Walter Shewhart, while others refer to it as PDSA, as evolved by W. Edwards Deming. Whatever the terminology, we often forget that this IS a cycle.

We write it in a linear fashion because that is the way our language operates. P stands for plan, right? But stop and think about it. Is “plan” a noun or a verb? Is it A plan, or TO plan? Understanding this nuanced difference makes all the difference in understanding the cycle.

Listen to this Post or Subscribe to the Podcast:

If PDSA is a cycle, where does it start?

According to the article Re-translating Lean From Its Origin by Jun Nakamuro, the actual Japanese figures used for what we call ‘standard work’ make it clear that the intent is not to start the improvement cycle at Plan, but rather, to start with Study. This makes a lot of sense if you stop to consider that nobody concocts a plan out of nothing; any plan starts from some issue, problem, dilemma, or conflict.

Think about your organization. Someone has identified unacceptable circumstances (however that is defined). Some amount of information has been gathered, either by studying the situation - or more often - anecdotally. Based upon this information and that degree of study, people decide to ACT and establish a PLAN - what exactly they’re going to do about it. We don’t really start at ‘Plan.’ We really start at ‘Study.’

This distinction is critical in keeping the cycle of PDSA turning because starting at ‘P’ leads to some unintended consequences.

This is no truer than when the issue is a dilemma and not a problem.

What’s the Difference Between a Problem and a Dilemma?

A problem has a solution; apply the solution and the problem goes away. Think: stuck with a flat tire, replace it - now you can keep going.

A dilemma has no such solution. Rather, it is a balancing act among valuable, but competing options. Starting with a plan that is somebody’s idea of what to do and then studying the result might work, but what happens when the notions of ‘success’ differ - when different people value options differently - when their ‘Check,’ the standard used to evaluate for success - is something different?

Each party comes up with a solution to the issue that addresses their definition of success, or failure. This leads to differing ideas about what will work and results in what I call ‘dueling solutions,’ as each party defends their own plan. This quagmire is a certain dead end to nowhere.

Plan as a Verb

What if Plan is really a verb? Study and Act now are integral parts of the ‘planning’ that goes into the subsequent ‘plan.’

The question then becomes how much planning? Too much is a waste of energy because there is no way to anticipate all the unintended consequences and unexpected results lurking inside even the best-devised plan. It is impossible to know what actually works until it is put into action. You have to actually try it to really find out - that is the beauty of PDSA, continuous improvement, and Kaizen. This provides a platform and a safe place to try, learn and evolve before fully committing to a choice that turns out to be misguided. But that means the Plan has to be tried.

In the book Drive, author Dan Pink looks at the social science research around motivation. He finds that it revolves around 3 elements:

- Purpose - a reason to act

- Mastery - the ability to act and desire to be better

- Autonomy - the time and space to figure out how to act in the service of the purpose.

No one would expect you to feel good about running a 30-foot waterfall in a kayak if you have never developed the skill to run a 5-foot drop or taken the time to scout the rapid and decide on the best line to take. Even if you had a good plan, you would probably not proceed without a good reason to do it.

In other words, you would not be motivated to participate in the act if there had not been sufficient planning so that you could accept the risk of a negative outcome, while still feeling reasonably confident the outcome you were hoping for would happen - the fabulous feeling that comes from achieving something challenging and worthwhile - success! (however that is defined).

Without enough Study, the Plan never gets off the ground. People don’t believe enough in the possibility to invest the energy to find out.

Sound familiar?

PDSA and the “Muslim Ban”

So having said all this, let’s look at this presidential directive. The word ‘Ban’ is defined in the dictionary as ‘stoppage, suppression, prohibition.’ On its face, it does not imply a time frame. Whatever the official document says, the administration’s explanation and language did not clearly spell out their intention, especially given the campaign rhetoric. That ambiguity left the plan open to various interpretations by people according to their own worldview. For many, the directive was not compatible enough with their notion of a successful solution to the problem of safety and security. In their view, the plan failed to acknowledge all the risks in what is really a dilemma. For them, it would never get a try.

This was a classic mistake of starting the cycle at ‘P’ and then working backward to defend that choice, rather than starting with ‘S’ and doing the right amount of study to conceive a plan worthy of being tested. The administration viewed Plan as a noun, rather than Plan as a verb. Their plan (P) was implemented (D) without the extreme vetting it needed to be seen as a viable enough option. Whatever ‘S’ had taken place, it had been used to justify the plan rather than to inform it.

What a difference it would have made to start at S!

S/A/P/D - careful analysis first to be sure the Plan would be acceptable enough so people would see it as something worthwhile enough to invest themselves in and be willing to participate in working through the iterations on the path to reveal an ideal change. Such study would have made it obvious ‘ban’ needed some clarification. Did ban mean everyone? What about green card holders and people who had risked their lives to support US troops? Would it even result in more safety, or less?

The funny thing is that the president’s first mention of such a ban during the campaign intended for a moratorium while the country figures out how to refine its vetting to be more effective. That sounds like PDSA to me. This would have allowed the cycle to keep turning and working toward a more workable solution over time. But did it require a ‘ban’ to do this sort of review? The president, however, made a campaign promise, used the term ‘ban,’ and boxed himself into a corner. This is what happens when you treat something as a problem with a simple solution, when it is really a dilemma whose resolution requires the balancing of many valuable, but competing perspectives.

Losing Credibility when the Cycle Goes Awry

As it now is, having started at ‘P’ the noun instead of ‘P’ the verb, we are again bogged down in dueling solutions, each party believing they know what is right and defending their own view. On all sides, brains are processing what they ‘believe’ and concluding their way is the only way. The brain attempts to carve a path through the unknown by forming a story to explain the circumstances using preconceptions and past experiences, deciding on a choice that best fits the story. But in failing to acknowledge that there are other valuable perspectives that matter, the brain runs the risk of starting at ‘P’ the noun. Differing concerns lead to differing stories and that results in conflict, resistance, and dueling solutions. Misguided choices abound. Sound familiar?

But that is not the worst of it. The more each party pushes their agenda, the less credibility and trustworthiness they are seen to have by those they are trying to convince and who see the issue differently. As we have seen in previous posts, credibility trumps reason. You may have the perfect answer, but if others don’t believe you have their concerns and success in mind, then nobody will hear or trust what you say or do. No one will give your plan a try.

The administration had to backtrack and try to define the terms - “it’s not really a ban.” “It doesn’t apply to green card holders.” They tried and had to Adjust, which is fine; after all that is part of PDSA, but they paid a huge credibility price for not having tested and vetted their plan sufficiently enough before going live. Starting at P the noun carries a real risk to your credibility. Not doing your due diligence at S really limits the ability to lead. Credibility matters.

So what to do?

When faced with dueling solutions, pounding away at your choice just does not get things moving forward. Oh sure, you may get your way, but the price you pay in credibility and slow implementation will all but derail your intentions down the road.

How much planning is enough- not too much, not too little? This is a dilemma, but there is a guidepost along the way. It’s called "the shared outcome" - the notion of ‘success’ that everyone does agree with. Although not always obvious, it certainly does exist. Maybe that is your organization’s mission statement. Maybe that is what everyone agreed to work toward, but has gotten lost in the logistics and details and agendas. This step alone will surface the misunderstandings in semantics and definitions, demonstrate an interest in other viewpoints, and get the ball rolling on track. ‘Shared outcome first’ ... S/A/P/D … THAT is the art of the deal.

Focus on the shared outcome and trust the options will emerge. There are always options; we just can’t always see them. And we are certainly blind to them when stuck in dueling solutions.

I will go out on a limb and say that everyone in the United States (and around the world) wants to feel secure. Everyone can rally behind safety. The question is what plan bests balances all the risks in trying to achieve that. Whether you agree or disagree that this presidential order represents an ideal change, I think it is safe to say the controversy surrounding it has limited its utility and diverted attention and energy away from the intended goal.

And what I can also safely say is that getting there is not a problem with an easy solution. It is a dilemma, like so much of what you confront in your organization each and every day.

Next time: "Vet the 'P' - A Guide To The Dilemma Of Planning." Subscribe to the blog to make sure you don't miss it!

About the Author:

Mark Jaben is a residency trained, board certified Emergency Physician with over 25 years of clinical experience. After 20 years in a single hospital group, he has been doing independent emergency medicine practice for the past 7 years in the community setting in emergency departments ranging from 5000- 75,000 annual visits and has experience in hospitals, Indian Health Service facilities, office practices, and EMS services. His initial immersion into Lean came in 2008 while living and working in Taupo, New Zealand, where he had the opportunity to test Lean methodology while leading implementation efforts at the hospital there. After returning to the US, he continued to apply these concepts in emergency departments, hospitals, clinics, and regional collaborations, with a particular focus on how this can inform individual work. Observing the successes, as well as the trials and tribulations, led Mark to delve further into why this stuff works. His soon to be released book, Free the Brain: Overcoming the Struggle People and Organizations Have With Change, takes a look at what neuroscience research says about how the brain operates and provides some real insight into why organizations do, or don’t, function so well.

Mark Jaben is a residency trained, board certified Emergency Physician with over 25 years of clinical experience. After 20 years in a single hospital group, he has been doing independent emergency medicine practice for the past 7 years in the community setting in emergency departments ranging from 5000- 75,000 annual visits and has experience in hospitals, Indian Health Service facilities, office practices, and EMS services. His initial immersion into Lean came in 2008 while living and working in Taupo, New Zealand, where he had the opportunity to test Lean methodology while leading implementation efforts at the hospital there. After returning to the US, he continued to apply these concepts in emergency departments, hospitals, clinics, and regional collaborations, with a particular focus on how this can inform individual work. Observing the successes, as well as the trials and tribulations, led Mark to delve further into why this stuff works. His soon to be released book, Free the Brain: Overcoming the Struggle People and Organizations Have With Change, takes a look at what neuroscience research says about how the brain operates and provides some real insight into why organizations do, or don’t, function so well.

Add a Comment