A root cause analysis is a structured method for finding the underlying causes of process problems and undesirable outcomes. Root cause analysis is a core problem-solving technique used by organizations dedicated to continuous improvement. As the name implies, it is all about addressing the causal factor rather than treating symptoms that address only surface problems. There are several analysis tools that teams of all types and sizes can apply to expedite problem-solving efforts.

What is a root cause analysis?

Fundamentally, a root cause analysis involves answering three broad questions about the sequence of events that leads to the issue using several structured methods:

- What is the problem?

-

Why did it occur?

-

How can it be prevented in the future?

In a continuous improvement culture, a root cause analysis is a standard intervention in any process, especially those where avoiding delays is essential. Short-term bandaids are replaced with solutions that address the root issue and result in long-term improvement.

Who conducts the root cause analysis?

A root cause analysis requires the right team and no people needlessly involved.

Typically, a root cause analysis team will include:

- A facilitator to set a plan and guide the participants through the analysis

- Team members involved in operating the process, more specifically those close to the incident

- The process owner for knowledge of the historical process

- One or more subject matter experts to interpret and implement solutions

- In some cases, the internal or external customer of the process can also be helpful.

The Core Principles of Root Cause Analysis

There are a few fundamental principles that inform effective root cause analysis. These will help the analysis achieve its aims; they will also help the team gain trust and buy-in from stakeholders, clients, or leadership.

- Focus on correcting and remedying root causes rather than just treating symptoms.

- It is OK to treat symptoms for short-term relief as long as the effort to find the root cause remains a high priority.

- Accept that there can be, and often are, more than one root cause.

- Prioritize how and why something happened, not who is to blame.

- Be analytical and find objective cause-effect evidence to back up root cause claims.

- Provide enough information to justify a corrective course of action.

- Document how a root cause can be prevented (or replicated) in the future.

When should you perform a root cause analysis?

The simplest way of thinking about it is that you should perform a root cause analysis whenever a problem repeatedly shows itself within a process. When that problem is causing unintended process results or hindering flow, it is necessary to dig deeper and uncover the heart of the problem. Six typical situations where a root cause analysis may be needed are:

- Safety concerns such as accidents or risk

- Quality control of production systems

- Sub-optimal business processes results

- Engineering failuresProduct defects or rework

- Process downtime

- Unpredictable process outputs

How is a root cause analysis performed?

To start, whatever method you use, the following steps are essential:

- Document each incident with a factually correct account and supporting images or documents

- Craft a detailed statement of the problem to be addressed

- Identify and collect data and reports that verify the account

- Develop a timeline of the incident/occurrence

- Brainstorm potential causes and remedies

- Apply countermeasure actions

- If the implemented solution does not work, start again until the solution is effective.

Here are some root cause analysis techniques you can employ:

1. The 5 Whys

The go-to method in the continuous improvement world is the 5 Whys analysis. It is merely a series of 'why' questions to get to the root cause. Here's an example:

Problem statement: The contact center wait times and abandon rates are too high.

Why? Contact center agents can not keep up with call volume.

Why? There was inadequate staff for the number of calls.

Why? The schedule did not account for increased pre-holiday calls.

Why? The system did not use last year's call volume to predict this situation.

Why? It was not programmed to do so.

By asking a repeated series of "why" questions, you can get to the core issue at hand, in this case, a poorly configured staffing system.

The system can be set up to analyze call volume to adjust staffing based on predictable events in the future.

While it is simple, the 5 Whys technique does require discipline and training. The team must know when to stop and take corrective action, in this case, fixing the programming error, rather than asking an infinite number of whys.

2. Fishbone / Ishikawa Analysis

For more complex problems, the fishbone analysis is a visual tool to map out the categories of potential causes. It then breaks each down into smaller categories which may be the root cause.

The categories are commonly, but not always:

- Maintenance

- Material

- Machine/technology

- Physical work

- Method/process

- Environment

It starts with a problem question such as "Why is our e-commerce cart abandon rate high?".

This forms the head of the "fish." The rest of the body flows from this question. The remainder of the fishbone includes several lines (the bones), representing various categories of questions to ask. You begin to form ideas around the causes and possible solutions for this root cause.

3. Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

FMEA is a technique to identify where and how failures might occur and the consequences.

Ideally, this is performed before the process goes live.

The steps are:

- Document the process by creating a flowchart of each step

- Suggest potential failures by looking at data and making a list of them

- List the impacts that may happen from each possible failure

- Rank the effects by their severity

- Create an action plan to correct these failures and monitor if they do indeed occur

4. Pareto Analysis

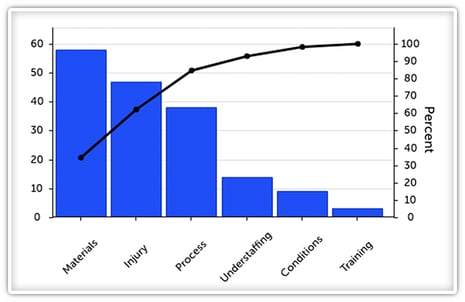

A Pareto chart consists of a bar and line. Each bar represents a category of defect/problem.

The bar's height represents a unit of measure, for example, frequency of occurrence or cost.

The bars are ordered from tallest to shortest, designed to visualize which problems have the most significant impact.

To undertake a Pareto analysis, you would follow these steps:

- Define the problem

- Identify the steps that build-up to the problem

- Plot each of the causes on a bar graph and on the X-axis

- Analyze each cause and determine the impact it has on the problem

- Quantify that impact with an objective score plotted on the Y-axis

- Complete this for each of the steps and arrange these based on their scores

- With this information gathered, you can identify the most effective change.

This technique is highly valuable when you have many possible courses of action, and you need to prioritize them.

5. Interviewing

While similar to the 5 Whys technique, the interviewing method, also called the interrogator/challenger interview, is a method that can be applied before using any of the other tools in this list.

It involves asking the process owner and other relevant stakeholders questions to learn more about their investment in the problem and their motivations.

Step 1: Clarify the problem

Step 2: Ask why the issue matters

Step 3: Ask why the reason above matters to them.

Step 4: Ask more questions of this nature until you can gauge their investment in the problem.

Use this technique thoughtfully. It can cause harm if the interviewee feels threatened or interprets your questions as aggressive. Be sure to use a tone that conveys interest in their experience, not blame.

Whether you choose one of these techniques or combine elements to develop your approach, the bottom line is simple. Finding the root cause of a problem is the only way to apply a lasting fix and avoid recurrence. Your continuous improvement culture and results will thrive when your team is empowered with the tools and skills to look beyond the surface.

Add a Comment