What Are the Most Effective Lean Six Sigma Tools for Process Improvement?

February 3, 2026Lean Six Sigma combines Lean’s system-wide approach to improving flow and quality with Six Sigma’s analytical tools for understanding...

What is Kanban and How Can It Transform Your Organization?

August 18, 2025There are dozens of tools and techniques used by organizations to support their continuous improvement efforts. The most successful...

The 5 M’s of Kaizen: A Practical Framework for Continuous Improvement Leaders

February 13, 2026We often describe Kaizen as a way of looking at the world rather than a prescription for achieving positive change. Kaizen thinkers seek to...

Kaizen Event Planning in 7 Simple Steps

December 5, 2024Here at KaiNexus, we get the opportunity to chat with organizations across all industries and write about many different continuous...

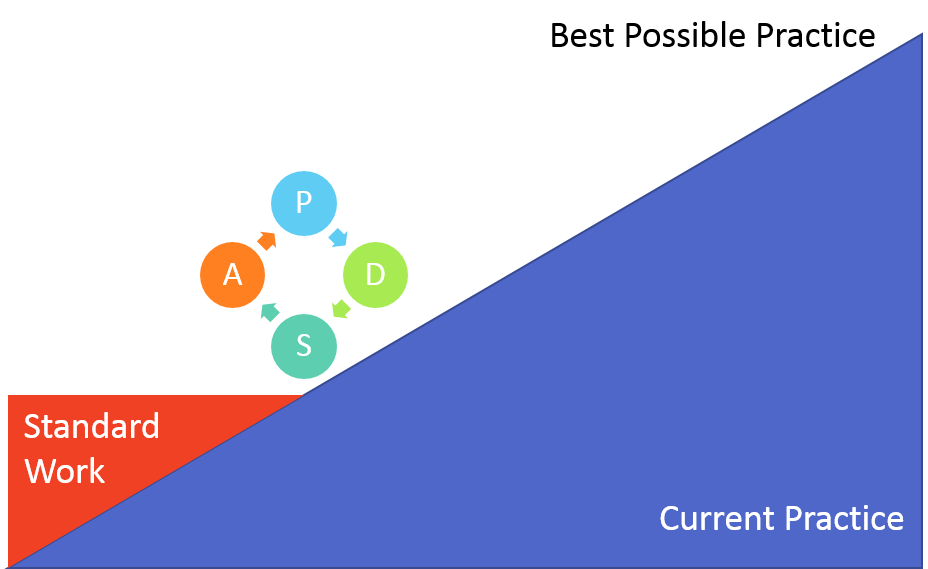

How Does Standard Work Drive Continuous Improvement in Organizations?

September 2, 2025Standard Work serves as the foundation for all continuous improvement efforts by establishing consistent, documented processes that create...

Kaizen Management: How to Build a Culture of Continuous Improvement

February 14, 2026Summary: Kaizen management builds a culture of continuous improvement by focusing on process over short-term goals, engaging employees as...

The Fundamental Principles of Kaizen Project Management

March 8, 2024The continuous improvement methodology of Kaizen was once closely associated with industrial and automotive manufacturing. That’s because...

Continuous Improvement Tools, Techniques, and Why You Need Them

July 17, 2023Continuous improvement is an ongoing effort to enhance processes, products, services, and overall business performance. It is a systematic...

Business Process Improvement (BPI): The Complete Guide to Methods, Tools, and Examples

February 14, 2026Business process improvement (BPI) is the systematic approach of analyzing, optimizing, and enhancing existing business processes to...